As a reader, I try to keep my TBR stack wide in its variety. At the moment, I’m reading the last Mark Twain book on my list, Short Stories and Tall Tales. On audio, I’m listening to Uncle Tom’s Cabin. As an editor, I keep thinking, “I wouldn’t publish any of these. They break all the rules.”

As a reader, I try to keep my TBR stack wide in its variety. At the moment, I’m reading the last Mark Twain book on my list, Short Stories and Tall Tales. On audio, I’m listening to Uncle Tom’s Cabin. As an editor, I keep thinking, “I wouldn’t publish any of these. They break all the rules.”

Except…Those weren’t the rules in 1857 or during the Gilded Age when Twain wrote. Stowe wasn’t a conscious stylist. She simply wrote what she knew of and put it out there for the reader to judge. This book makes me angry, which is what Stowe was going for. Twain, on the other hand, brought a newspaper man’s sensibility to storytelling, coupled with an ear for dialog and dialect and a talent for letting us know what the speaker sounded like. But Twain broke the rules of his day.

He wrote short, declarative sentences, in dialect, and in a conversational style that make him easy to imitate even though most people have never heard him speak. Doesn’t hurt he died recently enough that even older Millennials might have met someone whose parents actually heard him speak. But…

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn would not fly today, not in its current form. I don’t mean the embedded racism of society when Twain writes about. Newer versions have omitted a certain slur in favor of the word “slave” without any damage to the meaning. If anything, it drives the point home. What I do mean is you have to read that one out loud to know what Huck and Jim are actually saying. And therein lies the reason you did it back then and not now. Twain intended for his works to be read aloud or have them read aloud. In audio narration, you’d spend most of your time cringing at the characters attitudes (and realize Jim is waaaaay smarter than his vocabulary suggests), but the right reader would make you forget the dialect after about five minutes. Now? People sit and read in small sips, often on electronic devices. That use of apostrophes and well-placed malaprops that work so well out loud and on Audible suddenly become a barrier. It didn’t help Huck narrated the two later Tom Sawyer novels (which weren’t exactly classics.)

But Twain’s journalistic tendencies reshaped English literature. The heavy, ponderous, hard-to-read prose of the past (Looking at you, Henry James! You still owe me an apology.) gave way to crisp, visceral writing by a guy used to thinking in terms of column inches and above or below the fold on the front page. That brings us to Hemingway. And Raymond Chandler. Hemingway’s sentences were bullets. Very short. Get to the point. Sometimes fragments. On purpose. Chandler pioneered, then made cliche, the use of simile as a literary shorthand. Author Les Roberts, himself a decent crime writer whom I’ve had the pleasure of editing, sometimes parodies this in his own writing. One description of the month of April in Cleveland went on for a paragraph and ended with “was as urgent and persistent as the throbbing of an infected hangnail.” I almost stopped reading. Then laughed my ass off.

But Hemingway came up in the 1920s while Chandler began writing around 1930 (and shame on me if I missed any earlier short stories.) The world, roaring or in depression, moved quickly then and hasn’t slowed down since. The prose reflects that. Take the most famous American novel of all time, The Great Gatsby. I’ve read it. It packs a wallop. It’s less than 180 pages. Wow. Hemingway’s contemporary, F. Scott Fitzgerald, wrote that one. And his prose is even leaner than Hemingway’s.

And yet… I’d yank out most instances of “that.” I’m also aggressive about ripping out “very” and “just,” which have been overused to the point of near-uselessness. Gatsby has too much passive voice, too much description. Get to the point. Except Fitzgerald did get to the point. But he died before my mother was born, never mind me, and left behind one of the greatest American novels ever. Rules simply changed since.

Why? People still sat down and read books back then. They had radio, but no television. Most news came from newspapers. (I miss newspapers.)

Since the 1990s, though, editors started getting more aggressive. Passive voice was the enemy. (And yet that last sentence would likely pass muster.) They would cut the word “that,” along with “very” and especially “suddenly” without mercy. I myself get angry when I have to put “suddenly” back into a manuscript. I love my clients, but that word is so useless I’d rather keep an F bomb in a Sunday school primer than “suddenly.” And the dreaded run-on? Forget it. Run-ons must die.

Some of this is good. Some of this is a fad. We don’t write in dialect much anymore (Walter Mosley a stubborn exception), or we do with the lightest touch. Some of this is good. It makes the writing clearer for an audience with declining attention spans. And therein lies the issue.

Today, books and articles are competing with video games and TikTok and the Twitter clones. There are a lot more types of content out there, and the content itself has exploded exponentially. I myself read books usually 15 pages at a sitting. I have to. Like everyone else, I’m pulled in a dozen directions. Will they change again?

I’ve had the opportunity to spend some time with ChatGPT. Love it. Hate it. It will affect how we read and edit, too. (Also, it knows who Robert Fripp is. If this is Skynet, the apocalypse will have a killer soundtrack.)

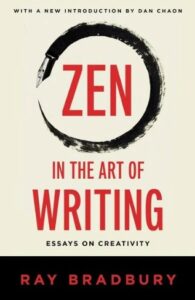

Ray Bradbury wrote a book about it. He came up in the age of pulps. His best known science fiction novel,

Ray Bradbury wrote a book about it. He came up in the age of pulps. His best known science fiction novel,  Writers get a lot of inspiration from music. From other writers. From poetry. It’s only natural they would want to quote it.

Writers get a lot of inspiration from music. From other writers. From poetry. It’s only natural they would want to quote it. I once read an email to another writer from a zine editor about how he handled manuscripts. “The first thing we do is cut. We cut and cut and cut.”

I once read an email to another writer from a zine editor about how he handled manuscripts. “The first thing we do is cut. We cut and cut and cut.”

Tom Clancy head hops like nobody’s business.

Tom Clancy head hops like nobody’s business.