As a writer, I have a love-hate relationship with my first published novel. I’m proud I wrote a solid PI tale set in my hometown of Cleveland. But I published badly, alienated an agent because of it, and also…

As a writer, I have a love-hate relationship with my first published novel. I’m proud I wrote a solid PI tale set in my hometown of Cleveland. But I published badly, alienated an agent because of it, and also…

There is too much damn swearing in that book. It’s out there now, still with Clayborn Press, but if I were to go to, say, Down & Out Books to republish it, I’d do a complete rewrite.

“Wait. Because of swearing?”

Yes and no. There’d still be swearing in it, but especially after taking on editing duties, I’ve found a lot of manuscripts have little swearing in them. And Marcus Sakey, an author with whom I was acquainted for a time, told me about his “F Bomb Check.” He took out every other F bomb, or every third one. I started doing that with my crime fiction. In scifi?

The Children of Amargosa was initially presented as a YA novel. By Storming Amargosa, that had gone into the rearview mirror. The moment it changed, however, came when I wrote Suicide’s rant to JT Austin about disobeying orders and joining the mission to find a fallen starship (a very Harry Potter thing to do in a story more like Lord of the Rings. With aliens. And dirty polygamists.*) JT, still reeling from his wife’s death, pleads a promise he made to take back her family’s farm. Suicide explodes, “F*** your promise, little boy! We all lost someone in this war!” It’s actually the only F bomb in Second Wave, but writing it was the moment I stopped pretending this was a YA series and JT forced himself to become an adult.

Meanwhile, Nick Kepler, my original PI character, needs a bleep button in his pocket. So, how much swearing is too much?

Most newer writers–That would be me in the early 2000s–use profanity to sound tough or earthy. But like Ralphie’s dad in A Christmas Story, you have to learn to work in foul language like some artists work in oils or water colors. It didn’t help us crime writers religiously watched The Wire, which had a writing staff composed partially of the cops the characters were based on, along with some of the criminals they tangled with. Cops and gang bangers tend to swear a lot, though having witnessed two less-than-pleasant encounters with police in the past year, I’ve noticed they tend to yell more than swear. At least in the suburbs.

So how do you handle swearing?

- Know thy audience. Yes, you’re free to say what you want how you want. You are not free from the consequences. No one is obligated to like your book or buy it. If your audience is primarily Sunday School teachers, you may want to avoid swearing altogether. But even hardened veterans who have been to Afghanistan or Syria tend to back down from the language. One veteran I know who writes scifi had a book where a female soldier was brutally raped by her captors. Leaving aside the question of how to handle such a scenario, the book had very little swearing or graphic depictions of violence (except in the sequel, where a corrupt admiral came to a sticky end. Don’t think he will ever mend.**)

- If you’re going to swear, do it on page 1, or at least in the first three pages. You don’t have to drop an F bomb. A mild profanity like “shit” will do. (Editing tool PerfectIt repeatedly tries to edit that out but doesn’t seem to care about F bombs for some reason.)

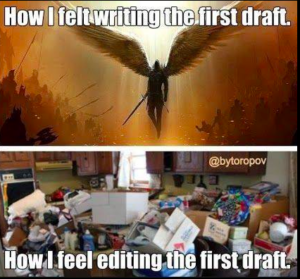

- Swear in the first draft. Clean up in revision. The rough draft is where your tough guy protagonist finishes fighting bad guys and stops off at the vet to pick up his pet unicorn because you were feeling goofy that day. Revision is where you might want to change that unicorn to a cat or a dog. The same with the language. Write whatever you want in the rough draft, even swearing so thick it would scare off Quentin Tarantino. Edit it out in revision. First draft is for you. Subsequent drafts are about the eventual audience.

- The F Bomb Check – Start with yanking every third one. Or every other one. You’ll find most of the time the prose and dialog are stronger for it.

- Don’t overthink it. If you put rules on it, you’ll just end up with stilted, flat prose. If you take the audience, the publisher, or even your own preferences into account, you can easily modify what you’ve written in revision. Revisions should not be scary. They should be making your story better.

*It’s a lot more complicated than that. Even polygamists who bathed often didn’t like these guys.

**Apologies to the late John Entwistle

As a reader, I try to keep my TBR stack wide in its variety. At the moment, I’m reading the last Mark Twain book on my list, Short Stories and Tall Tales. On audio, I’m listening to Uncle Tom’s Cabin. As an editor, I keep thinking, “I wouldn’t publish any of these. They break all the rules.”

As a reader, I try to keep my TBR stack wide in its variety. At the moment, I’m reading the last Mark Twain book on my list, Short Stories and Tall Tales. On audio, I’m listening to Uncle Tom’s Cabin. As an editor, I keep thinking, “I wouldn’t publish any of these. They break all the rules.” This is the part where you go, “Huh?”

This is the part where you go, “Huh?”

Elmore Leonard once said of exclamation points, “You are allowed no more than three per 100,000 words.”

Elmore Leonard once said of exclamation points, “You are allowed no more than three per 100,000 words.”

Thanks to clickbait and social media, use of the apostrophe (or “sky comma”) is a lost art. The most common (and often ridiculed) error is, of course, your/you’re. When you’re typing at a million miles an hour and want the words down, it’s easy to “hear” a word and pick the wrong spelling. For all the jokes about your/you’re, it’s something a ninth grader doing a proofread of your manuscript can spot. Assuming that ninth grader doesn’t believe texting should be the basis of grammar. Spoiler alert: It shouldn’t. k thx bye!

Thanks to clickbait and social media, use of the apostrophe (or “sky comma”) is a lost art. The most common (and often ridiculed) error is, of course, your/you’re. When you’re typing at a million miles an hour and want the words down, it’s easy to “hear” a word and pick the wrong spelling. For all the jokes about your/you’re, it’s something a ninth grader doing a proofread of your manuscript can spot. Assuming that ninth grader doesn’t believe texting should be the basis of grammar. Spoiler alert: It shouldn’t. k thx bye! Back in the old days, when my dad would take us all out in his LaSalle to the five-and-dime for a grape Nehi while Rudy Vallee warbled “Whole Lotta Love”… Um… Wait. They didn’t make LaSalles when my dad was born, Rudy Vallee had given way to big bands, and my earliest memory of a new song was “Something” by the Beatles when I still had not known the horror of kindergarten. Let’s start again.

Back in the old days, when my dad would take us all out in his LaSalle to the five-and-dime for a grape Nehi while Rudy Vallee warbled “Whole Lotta Love”… Um… Wait. They didn’t make LaSalles when my dad was born, Rudy Vallee had given way to big bands, and my earliest memory of a new song was “Something” by the Beatles when I still had not known the horror of kindergarten. Let’s start again.